What Are You Reading?: Chris Washington

We're excited to continue our "What are you reading?" series by presenting an interview with Chris Washington, Assistant Professor of English at Francis Marion University. His first monograph, Romantic Revelations: Visions of Post-Apocalyptic Hope and Life in the Anthropocene, was published by the University of Toronto Press in September 2019. With Anne McCarthy he is co-editor of the collection Romanticism and Speculative Realism (Bloomsbury, 2019). He has published essays in Romantic Circles Praxis, Essays in Romanticism, European Romantic Review, Romantic Circles Pedagogy Commons, Literature Compass, and has several more forthcoming in journals and collections. He is also the editor of the forthcoming volume of essays, “Teaching Romanticism in the Anthropocene,” for Romantic Circles Pedagogy Commons. He is currently working on two monographs, “#OccupyRomanticism: Revolutionary Climate Protest from Then to Now,” and “Quantum Romanticism: Life, Love, and Politics in a World without Us.”

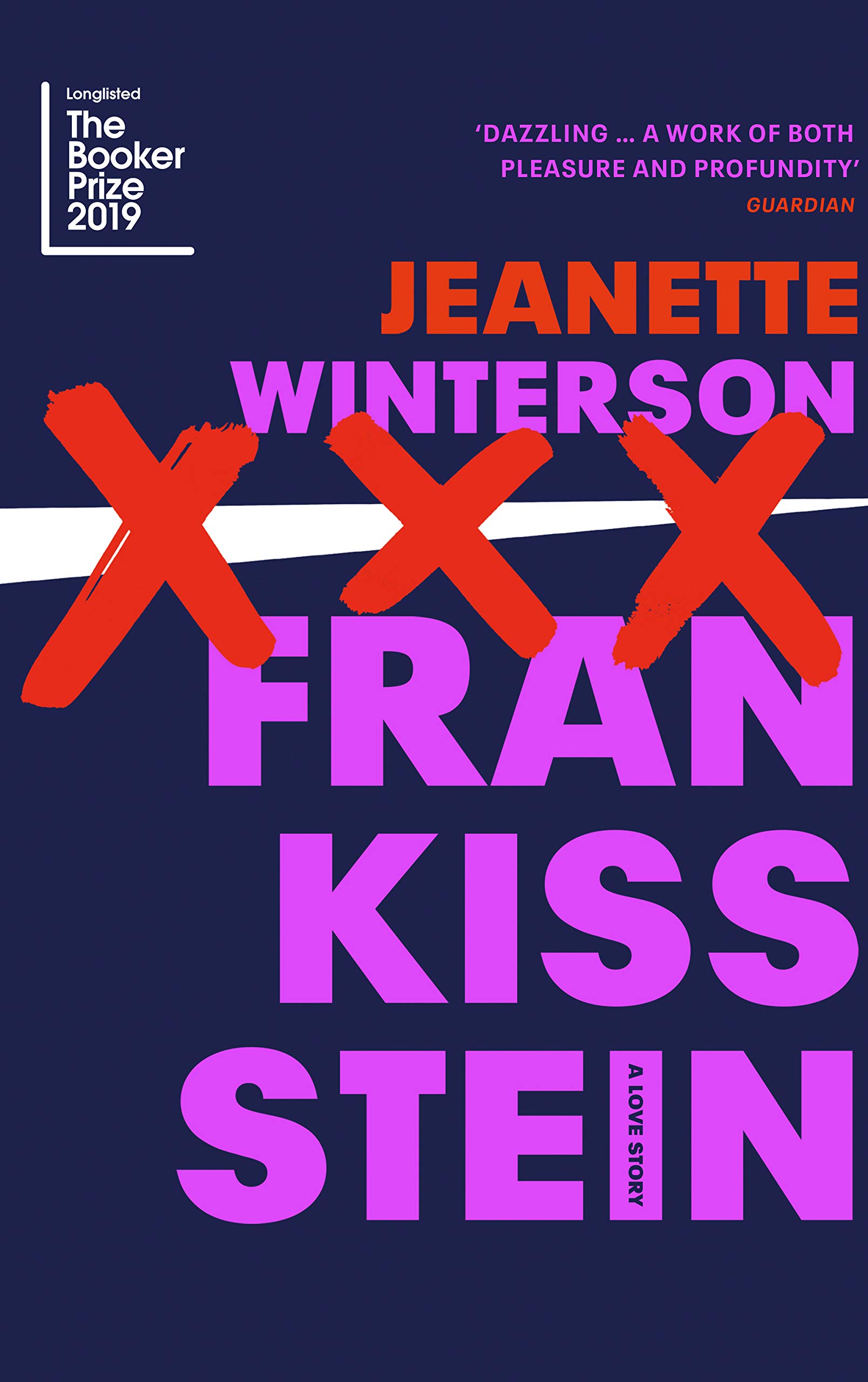

What new studies of Romantic literature are you reading right now?I’ve recently been reading and rereading Kate Singer’s Romantic Vacancy: The Poetics of Gender, Affect, and Radical Speculation, which I find fascinating and has helped me rethink how I think what Romanticism is, and can be, as well as providing new ways for me to think about how to write in general and how to write good scholarship in particular. I’m really taken by the notion that, as Singer puts it, “vacancy opens a non-binary landscape of transgressive figurative motions,” which has made me see Romantic gender and sexuality anew and has proven very influential as I conceive of one of the books I am writing. For two different projects, I’ve also went back to earlier studies, David Sigler’s Sexual Enjoyment in British Romanticism: Gender and Psychoanalysis, 1753-1835 and Anne McCarthy’s Awful Suspension: Suspension and the Sublime in Romantic and Victorian Poetry. Sigler’s work on sexuality charts out a much different Romanticism than I expected—and a most welcome one. Similarly, McCarthy’s book revises our long-held notions of the sublime and this has led me down new philosophical paths.A whole slew of books are on deck next. First, a book I am slated to review, Amanda Jo Goldstein’s Sweet Science: Romantic Materialism and the New Logics of Life. After that, another book I hope to review, Richard Sha’s Imagination and Science in Romanticism. In the meantime, for my own research, I have just finished Robbie Richardson’s wonderful The Savage and Modern Self: North American Indians in Eighteenth-Century British Literature and Culture and will be picking up Nikki Hessell’s Romantic Literature and the Colonized World and Philip Dickinson’s Romanticism and Aesthetic Life in Postcolonial Writing next.What’s the critical book that figured most significantly in your most recent monograph?This question is difficult to answer with any one particular book because Romantic Revelations launched from a variety of reading over many years and it is difficult to pinpoint a single book that was ping ponging around in my head over all of that time. Instead, I would have to mention a bricolage of authors whose works—either in critical books or articles—seemed to preoccupy me while I wrote the book: Jacques Derrida, Kate Singer, Emmanuel Levinas, Paul de Man, Sara Guyer, Claire Colebrook, David Collings, Karen Barad, Joel Faflak, Anne McCarthy, Marjorie Levinson, Alan Vardy, Graham Harman, Anahid Nersessian, and Quentin Meillassoux. And probably quite a few others I am not thinking of right in this now.Can you sum up your monograph in 10 words: why should we read it?I show how hope emerges from hopelessness—perfect for now!How will this publication and all the research you’ve carried out for it continue to inform your teaching?Most recently, I taught a course called “Romanticism and the Anthropocene” that took its basis from the book’s premise that post-apocalyptic Romanticism, although we think of it as a nihilistic end of the world, is really about hope and the hope of finding new ways of being and living in the present. So, we started with that premise as well as thinking about what Romanticism has to say about climate change and the environment before venturing away from the book for new worlds. Romantic Revelations is somewhat canonical in that its jumping-off point is M.H. Abrams’s idea that Romanticism is essentially apocalyptic—that is, a quest for a return to paradise—which he reads through figures like Wordsworth and Percy Shelley. The book departs from this narrative to show how Romanticism also nurtures a darker, post-apocalyptic heart featuring visions of a world after disaster, when no return to a mythical paradise is possible. The fallout from that scenario is that we have to configure a new politics for living after disaster. To that end, that is, responding to Abrams’s field-defining narrative, my main concerns in the book are with canonical figures like the Shelleys, Byron, and even Jane Austen (although I have a chapter on Clare too). By reading Shelley’s Frankenstein and Austen’s Pride and Prejudice as dialectical alternate universe versions of each other, though, I try to counter-read the canon in a way that opens it up in new ways.My class pushed this counter-reading of the canon even further even as we tried to be differently incorporative in terms of authors. So while we read authors like the Shelleys and Byron, and even some Clare, we turned toward others who still remain understudied by comparison. For example, we read Felicia Hemans, L.E.L., Mary Robinson, Mary Prince, Phillis Wheatley, Ouladah Equiano, and The Woman of Color by anonymous. Future classes would continue to pursue similar pathways as I keep trying to fully conceive my next project that I am calling “#OccupyRomanticism: Revolutionary Climate Protest from Now to Then.”What part of your reading of the criticism on the subject of apocalypse has been crucial to your study? For students interested in this subject, where would you send them first?In terms of apocalypse, I would say that the best place to begin is with The Book of Revelations from the Bible and then, in terms of Romanticism, Abrams’s Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature. Steven Goldsmith’s Unbuilding Jerusalem: Apocalypse and Romantic Representation and Ross Woodman’s and Joel Faflak’s Revelation and Knowledge: Romanticism and Religious Faith would be next. Nersessian’s Utopia, Ltd., while not on apocalypse, will also be of interest on this topic.Criticism on post-apocalypse, on the other hand, which is really the subject of my book, would be a different story, one more difficult to answer since relatively few studies attend to the topic as of yet.Which book do you most frequently recommend to your students? Which students? Why?Probably Shelley’s Frankenstein and Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Primarily, I recommend both to students in any of my literature classes for majors and non-majors. I think both of them present stunning ways of understanding the world that continually renew themselves the more we read them. In some sense, even, they find us as much as we find them, a kind of creating of difference that remakes that difference again and again through continual reading.What books are in your "to read next" pile right now? (poetry, fiction, theory, anything!) What might this tell us about where your research is headed next?A lot of my future reading is exploratory for one of two monographs I am currently working on. Right now I am focusing on “#OccupyRomanticism.” It argues that revolutionary Romantic ideas can inform and be informed by contemporary protest movements like Extinction Rebellion, Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, and #MeToo. I try to show how this presentist intersectionality models ideas and strategies for achieving inclusive environmental justice for the marginalized and oppressed, both human and nonhuman, as well as championing racial, indigenous, queer, and non-binary identities. It is very much an ongoing work informed by a variety of perspectives and theoretical approaches that I am continuing to discover and learn from. My hope is that the dialogue I weave together throughout these chapters between Romanticism and contemporary thinkers sketches a communal politics for living through the climate wars of the future. So, you know, very modest. It probably will end up as nothing other than a thought experiment.Current reading reflects research for that monograph: M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!; Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance; Dino Gilo-Whitaker’s As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock; Morgan Parker’s poetry; Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s From #Black Lives Matter to Black Liberation; and Julian Gill-Peterson’s History of the Transgender Child.I’m also rereading Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s M Archive: After the End of the World. In terms of current novels, Ali Smith’s How To Be Both and Richard Powers’s The Overstory.Soon I plan to read the recently-passed and much-missed Sean Bonney’s collection Our Death.And, like everyone else, Sally Rooney’s Normal People some time soon.Have there been any mainstream articles or publications on the Romantics you’d like to draw our attention to?I found Jeannette Winterson’s novel Frankissstein to be a marvelous read and am writing about it in my next monograph in relation to the non-binary in Shelley’s Frankenstein. I found the live reading of Frankenstein last year to celebrate its bicentennial a fantastic event to champion and spread the word on Romanticism.

What new studies of Romantic literature are you reading right now?I’ve recently been reading and rereading Kate Singer’s Romantic Vacancy: The Poetics of Gender, Affect, and Radical Speculation, which I find fascinating and has helped me rethink how I think what Romanticism is, and can be, as well as providing new ways for me to think about how to write in general and how to write good scholarship in particular. I’m really taken by the notion that, as Singer puts it, “vacancy opens a non-binary landscape of transgressive figurative motions,” which has made me see Romantic gender and sexuality anew and has proven very influential as I conceive of one of the books I am writing. For two different projects, I’ve also went back to earlier studies, David Sigler’s Sexual Enjoyment in British Romanticism: Gender and Psychoanalysis, 1753-1835 and Anne McCarthy’s Awful Suspension: Suspension and the Sublime in Romantic and Victorian Poetry. Sigler’s work on sexuality charts out a much different Romanticism than I expected—and a most welcome one. Similarly, McCarthy’s book revises our long-held notions of the sublime and this has led me down new philosophical paths.A whole slew of books are on deck next. First, a book I am slated to review, Amanda Jo Goldstein’s Sweet Science: Romantic Materialism and the New Logics of Life. After that, another book I hope to review, Richard Sha’s Imagination and Science in Romanticism. In the meantime, for my own research, I have just finished Robbie Richardson’s wonderful The Savage and Modern Self: North American Indians in Eighteenth-Century British Literature and Culture and will be picking up Nikki Hessell’s Romantic Literature and the Colonized World and Philip Dickinson’s Romanticism and Aesthetic Life in Postcolonial Writing next.What’s the critical book that figured most significantly in your most recent monograph?This question is difficult to answer with any one particular book because Romantic Revelations launched from a variety of reading over many years and it is difficult to pinpoint a single book that was ping ponging around in my head over all of that time. Instead, I would have to mention a bricolage of authors whose works—either in critical books or articles—seemed to preoccupy me while I wrote the book: Jacques Derrida, Kate Singer, Emmanuel Levinas, Paul de Man, Sara Guyer, Claire Colebrook, David Collings, Karen Barad, Joel Faflak, Anne McCarthy, Marjorie Levinson, Alan Vardy, Graham Harman, Anahid Nersessian, and Quentin Meillassoux. And probably quite a few others I am not thinking of right in this now.Can you sum up your monograph in 10 words: why should we read it?I show how hope emerges from hopelessness—perfect for now!How will this publication and all the research you’ve carried out for it continue to inform your teaching?Most recently, I taught a course called “Romanticism and the Anthropocene” that took its basis from the book’s premise that post-apocalyptic Romanticism, although we think of it as a nihilistic end of the world, is really about hope and the hope of finding new ways of being and living in the present. So, we started with that premise as well as thinking about what Romanticism has to say about climate change and the environment before venturing away from the book for new worlds. Romantic Revelations is somewhat canonical in that its jumping-off point is M.H. Abrams’s idea that Romanticism is essentially apocalyptic—that is, a quest for a return to paradise—which he reads through figures like Wordsworth and Percy Shelley. The book departs from this narrative to show how Romanticism also nurtures a darker, post-apocalyptic heart featuring visions of a world after disaster, when no return to a mythical paradise is possible. The fallout from that scenario is that we have to configure a new politics for living after disaster. To that end, that is, responding to Abrams’s field-defining narrative, my main concerns in the book are with canonical figures like the Shelleys, Byron, and even Jane Austen (although I have a chapter on Clare too). By reading Shelley’s Frankenstein and Austen’s Pride and Prejudice as dialectical alternate universe versions of each other, though, I try to counter-read the canon in a way that opens it up in new ways.My class pushed this counter-reading of the canon even further even as we tried to be differently incorporative in terms of authors. So while we read authors like the Shelleys and Byron, and even some Clare, we turned toward others who still remain understudied by comparison. For example, we read Felicia Hemans, L.E.L., Mary Robinson, Mary Prince, Phillis Wheatley, Ouladah Equiano, and The Woman of Color by anonymous. Future classes would continue to pursue similar pathways as I keep trying to fully conceive my next project that I am calling “#OccupyRomanticism: Revolutionary Climate Protest from Now to Then.”What part of your reading of the criticism on the subject of apocalypse has been crucial to your study? For students interested in this subject, where would you send them first?In terms of apocalypse, I would say that the best place to begin is with The Book of Revelations from the Bible and then, in terms of Romanticism, Abrams’s Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature. Steven Goldsmith’s Unbuilding Jerusalem: Apocalypse and Romantic Representation and Ross Woodman’s and Joel Faflak’s Revelation and Knowledge: Romanticism and Religious Faith would be next. Nersessian’s Utopia, Ltd., while not on apocalypse, will also be of interest on this topic.Criticism on post-apocalypse, on the other hand, which is really the subject of my book, would be a different story, one more difficult to answer since relatively few studies attend to the topic as of yet.Which book do you most frequently recommend to your students? Which students? Why?Probably Shelley’s Frankenstein and Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Primarily, I recommend both to students in any of my literature classes for majors and non-majors. I think both of them present stunning ways of understanding the world that continually renew themselves the more we read them. In some sense, even, they find us as much as we find them, a kind of creating of difference that remakes that difference again and again through continual reading.What books are in your "to read next" pile right now? (poetry, fiction, theory, anything!) What might this tell us about where your research is headed next?A lot of my future reading is exploratory for one of two monographs I am currently working on. Right now I am focusing on “#OccupyRomanticism.” It argues that revolutionary Romantic ideas can inform and be informed by contemporary protest movements like Extinction Rebellion, Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, and #MeToo. I try to show how this presentist intersectionality models ideas and strategies for achieving inclusive environmental justice for the marginalized and oppressed, both human and nonhuman, as well as championing racial, indigenous, queer, and non-binary identities. It is very much an ongoing work informed by a variety of perspectives and theoretical approaches that I am continuing to discover and learn from. My hope is that the dialogue I weave together throughout these chapters between Romanticism and contemporary thinkers sketches a communal politics for living through the climate wars of the future. So, you know, very modest. It probably will end up as nothing other than a thought experiment.Current reading reflects research for that monograph: M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!; Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance; Dino Gilo-Whitaker’s As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock; Morgan Parker’s poetry; Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s From #Black Lives Matter to Black Liberation; and Julian Gill-Peterson’s History of the Transgender Child.I’m also rereading Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s M Archive: After the End of the World. In terms of current novels, Ali Smith’s How To Be Both and Richard Powers’s The Overstory.Soon I plan to read the recently-passed and much-missed Sean Bonney’s collection Our Death.And, like everyone else, Sally Rooney’s Normal People some time soon.Have there been any mainstream articles or publications on the Romantics you’d like to draw our attention to?I found Jeannette Winterson’s novel Frankissstein to be a marvelous read and am writing about it in my next monograph in relation to the non-binary in Shelley’s Frankenstein. I found the live reading of Frankenstein last year to celebrate its bicentennial a fantastic event to champion and spread the word on Romanticism.