The Myth of History and Coleridge’s Caribbean Bath

By Alexandra L. Milsom, Hostos Community College, CUNY

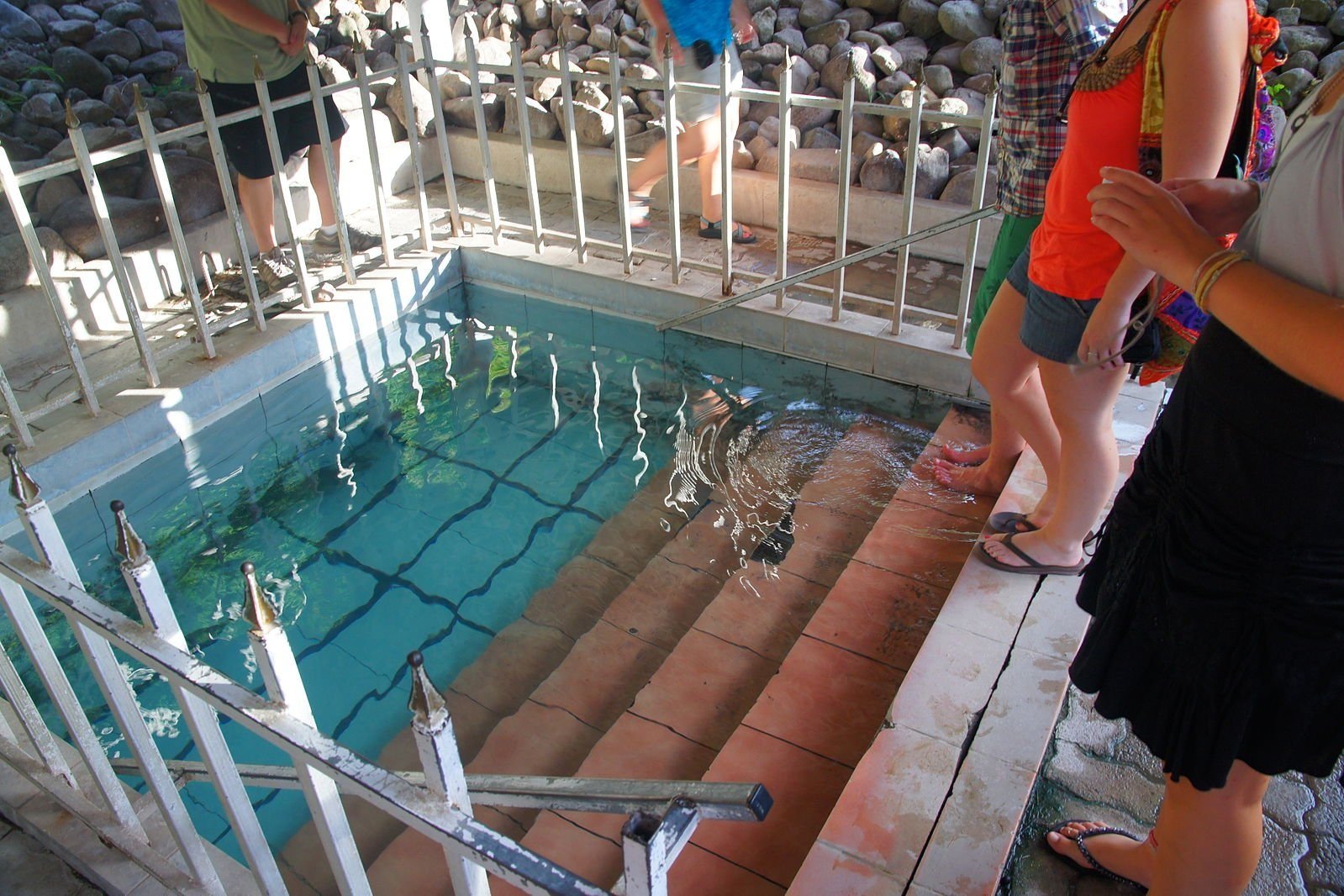

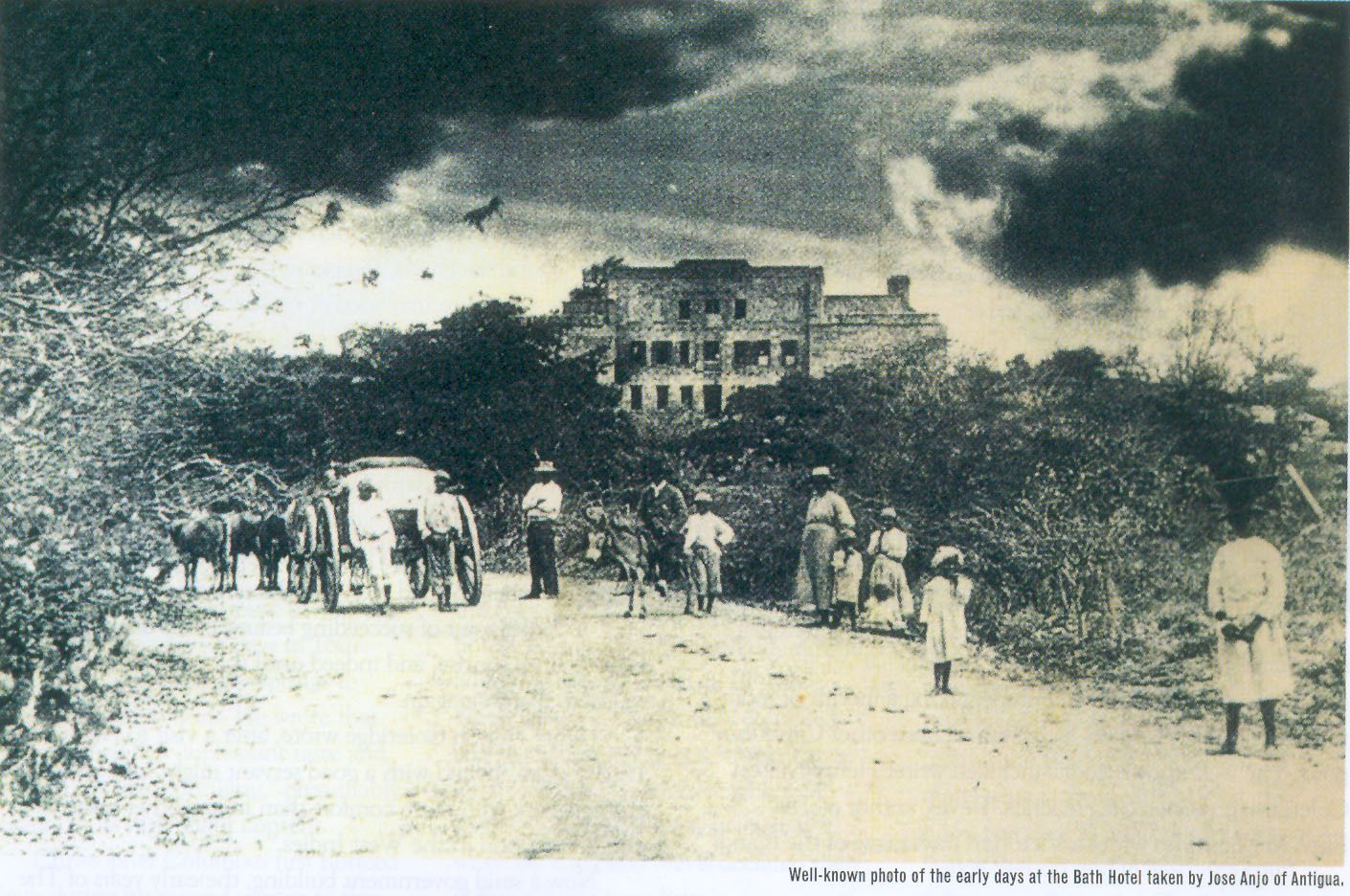

Ten years ago, Necee Regis wrote in the Washington Post that sharing her love of vacations in Nevis with other travelers was like “shaking a secret handshake in a club.” Like nearly every commercial and journalistic piece I have found that promotes Nevis to tourists, Regis’s article names Samuel Taylor Coleridge as an early visitor to the island’s “therapeutic hot springs.” She lists Coleridge and then a British monarch as visitors, as if associating the island with such illustrious guests authenticates it as a destination with a particular sort of elite and cultural clout.

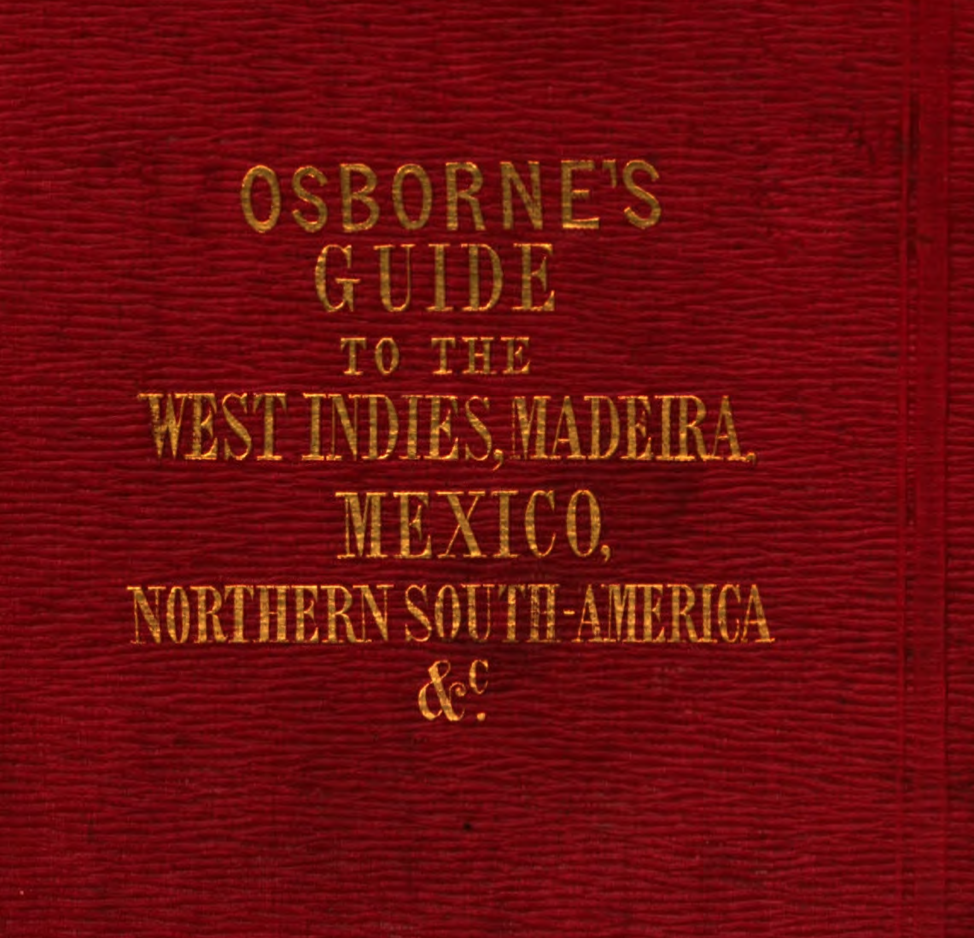

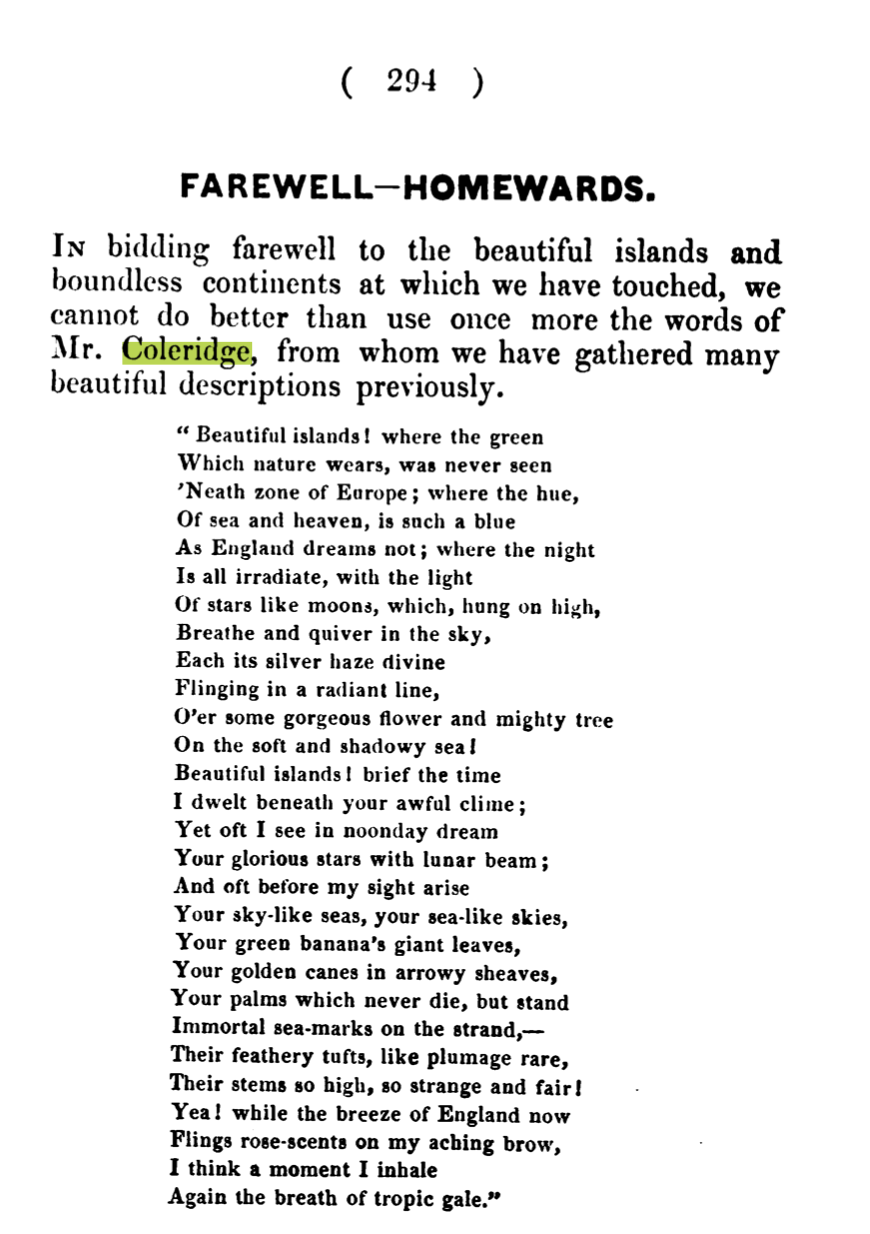

The fact is that Samuel Taylor Coleridge never visited Nevis, let alone the Caribbean. The story of Coleridge’s trip to Nevis endures because of a Victorian guidebook that fails to mention, probably on purpose, that the first name of the Coleridge who did, in fact, visit Nevis was “Henry.” Henry Nelson Coleridge – the poet’s nephew (and son-in-law)—memorialized his own voyage in an 1832 volume entitled Six Months in the West Indies in 1825. If Coleridge—any old Coleridge—can still be invoked to sell a Caribbean vacation to people who might not even read Romantic poetry, then it remains financially advantageous to keep using the story of his bath. Doing so perpetuates a profitable colonial fantasy and relies heavily on the authority still conferred by the English literary canon.

A colonial fantasy that can still sell tickets to today’s tourist implicates a Romanticism that still centers England, lionizes its literary celebrities, and avoids mentioning the unpalatable violence of empire as much as possible. In “Novel and History: Plot and Plantation,” Sylvia Wynter argues that lying about history in this way has always been profitable, which is why it persists. She explains, “The world had to be kept safe for the market economy. History, to help in this task, had to be distorted. The myth of history was used by the plantation to keep its power secure.”[1] Today, that very “myth of history” encourages tourists to ignore, or at best politely deplore, the history of enslavement and the poverty that persists in these tourist destinations.

[1] Sylvia Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Savacou 5 (1971): 100-101.

About the Author

Alexandra L. Milsom is an Assistant Professor of English at Hostos Community College, CUNY. She specializes in Romanticism, Victorian Literature, and tourism. You can find her publications in Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, the Keats-Shelley Journal, and Studies in Romanticism.