On Medicine Considered as One of the Fine Arts

Friday, October 22nd, 2027

Heyman Center for the Humanities at Columbia

Project leader: Arden Hegele (Columbia)

Collaborators: Lilith Todd (U Penn), Matt Sandler (Columbia), Erik Gray (Columbia)

Description

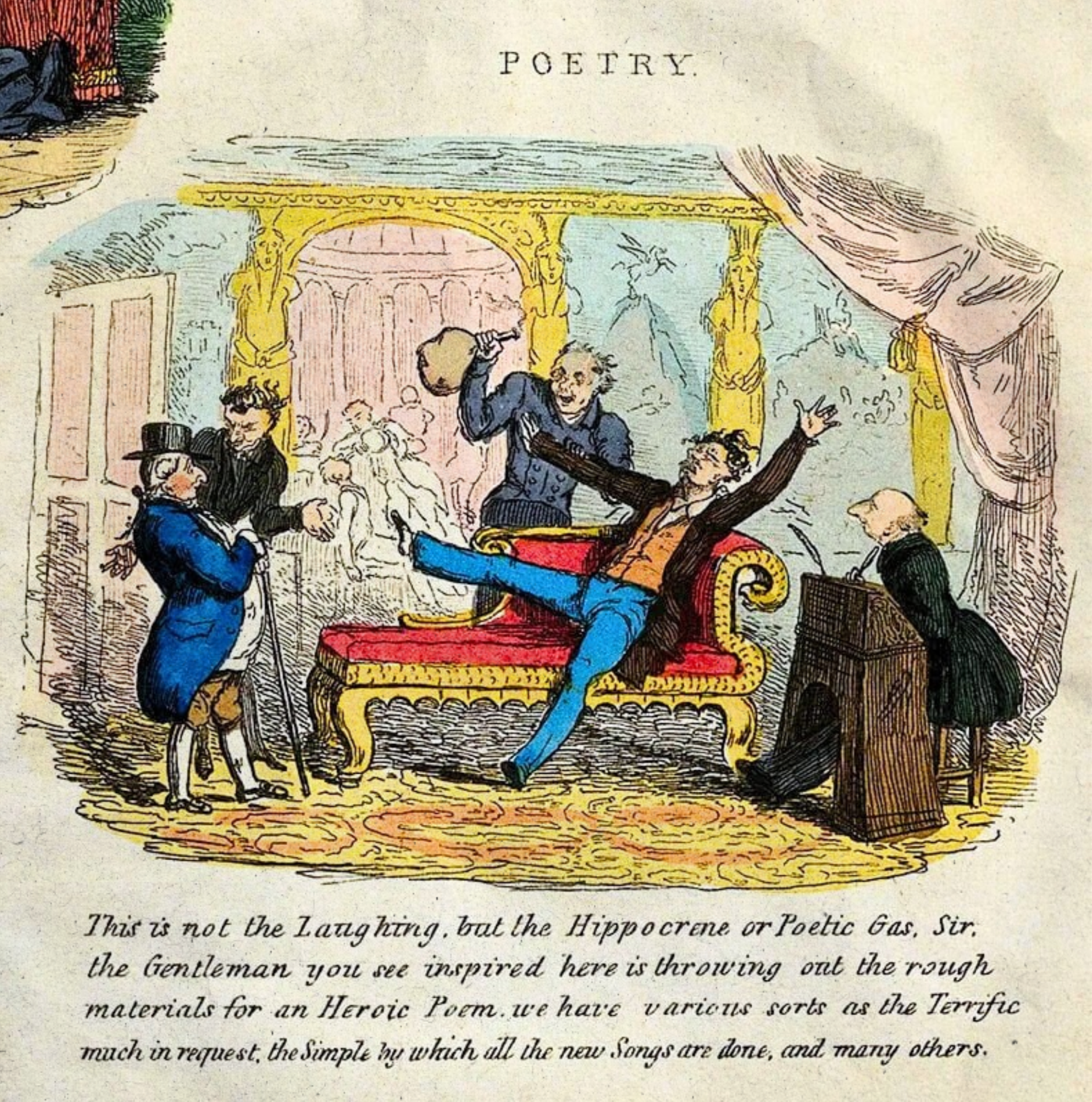

The relationship of poetry to medicine is an ancient association that intensely preoccupied Keats, Shelley, and their circles. In ancient Greece, the god Apollo was the deity of both poetry and medicine. In the 11th-century medieval Islamic world, the physician-writer Ibn Sina (Avicenna) argued in his masterwork, The Cure, that the writer must become “a doctor of the soul.” Yet in the Romantic period, conceptual inter-linkages between medicine and poetry were deepened and interrogated in new ways. Even as medicine was historically finding its feet as a standalone academic discipline, the writers and poets of British Romanticism were taking seriously the notion that poetic experimentation might have a measurable effect on transforming human bodies—both of poets and of readers. This conference will explore how the second-generation Romantics—especially Keats, Percy and Mary Shelley, Byron, Hunt, De Quincey, and others—attempted serious sallies into the history of medicine through their experiments in poetry.

Keats, Shelley, and their circles relished how the porousness between poetry and medicine allowed them to make unexpected interventions across the two cultures. Keats’ training under the great surgeon Sir Astley Cooper—documented visually in his medical-school notes and drawings—famously influenced his depiction of neural networks, the “wreath’d trellis of a working brain,” in Ode to Psyche. Shelley was a lifelong experimentalist of the thresholds and limits of the body; his tutoring under James Lind and reading of Erasmus Darwin spurred him to undertake his own physical trials with electricity, gunpowder, telescopes, and balloons. Byron, who had a longstanding interest in forensic and morbid anatomy, cast his vote for the Professor of Anatomy at Cambridge; later, he attended executions and visited the anatomical museums of Bologna, where he was amused to discover specimens collected by a female professor. In his Italian exile, Byron was visited by the poet-polymath Humphry Davy, who was about to be named President of the Royal Society, and they spoke about Davy’s landmark experiments in chemistry. In 1820, at the Palazzo Lanfranchi in Pisa (the future residence of both Byron and Hunt), Mary Shelley requested an Italian surgeon to perform a secret galvanic demonstration in the basement, influencing her revisions to the second edition of Frankenstein. And De Quincey’s 1827 On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts—whose bicentenary is in 2027—used simile and satire to explore the close figural relationship between the arts and the burgeoning medical field of forensics. The legacies of the Keats-Shelley circle in medicine today are both concrete and manifold: an established tradition of literary writing by doctors has drawn productively on the example of Keats as a foundational physician-poet, while the newer field of Narrative Medicine, taught within medical schools, regularly selects texts by the Romantic poets and other nineteenth-century writers, such as Mary Seacole, as it teaches physicians how to read and listen closely and attentively.

This conference, “On Medicine Considered as One of the Fine Arts,” is designed to address audiences on multiple levels. It aims to reach, at the entry level, high school and undergraduate students, as well as members of the general public, who may be curious about Romantic poetry; physicians and other health providers who are interested in how medicine finds its voice in literature and writing; and, finally, scholars and teachers who are interested in linking how the poetry and prose of British Romanticism might connect with contemporary writing about illness and the body. How can the Romantics offer us a model for enriching our own interdisciplinary pursuits today?

Look forward to more details soon!